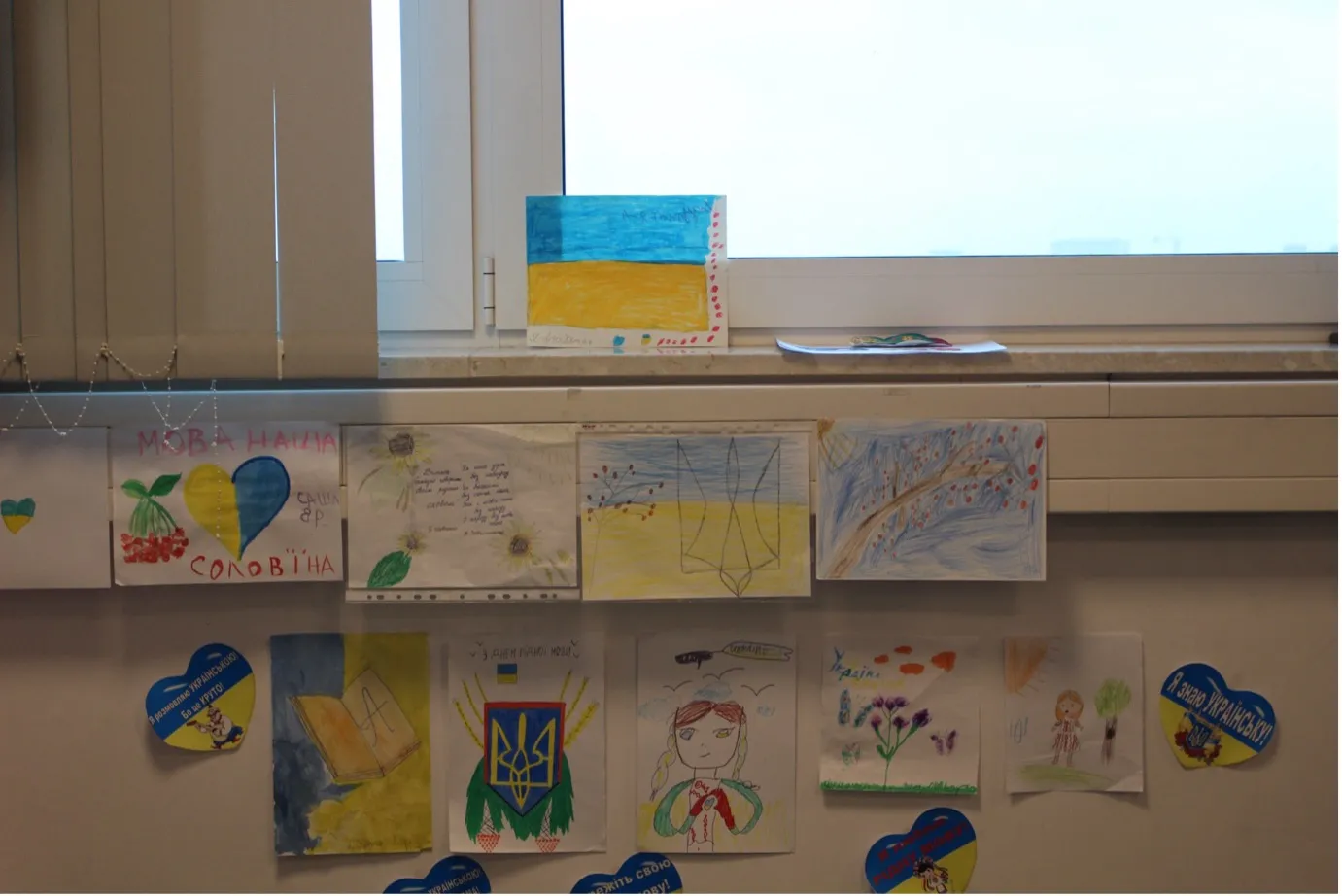

The strength and determination from each Ukrainian educator and child perfectly captures the spirit of these displaced families. None of these children or families chose this new reality, yet they have had no choice but to accept it and settle in.

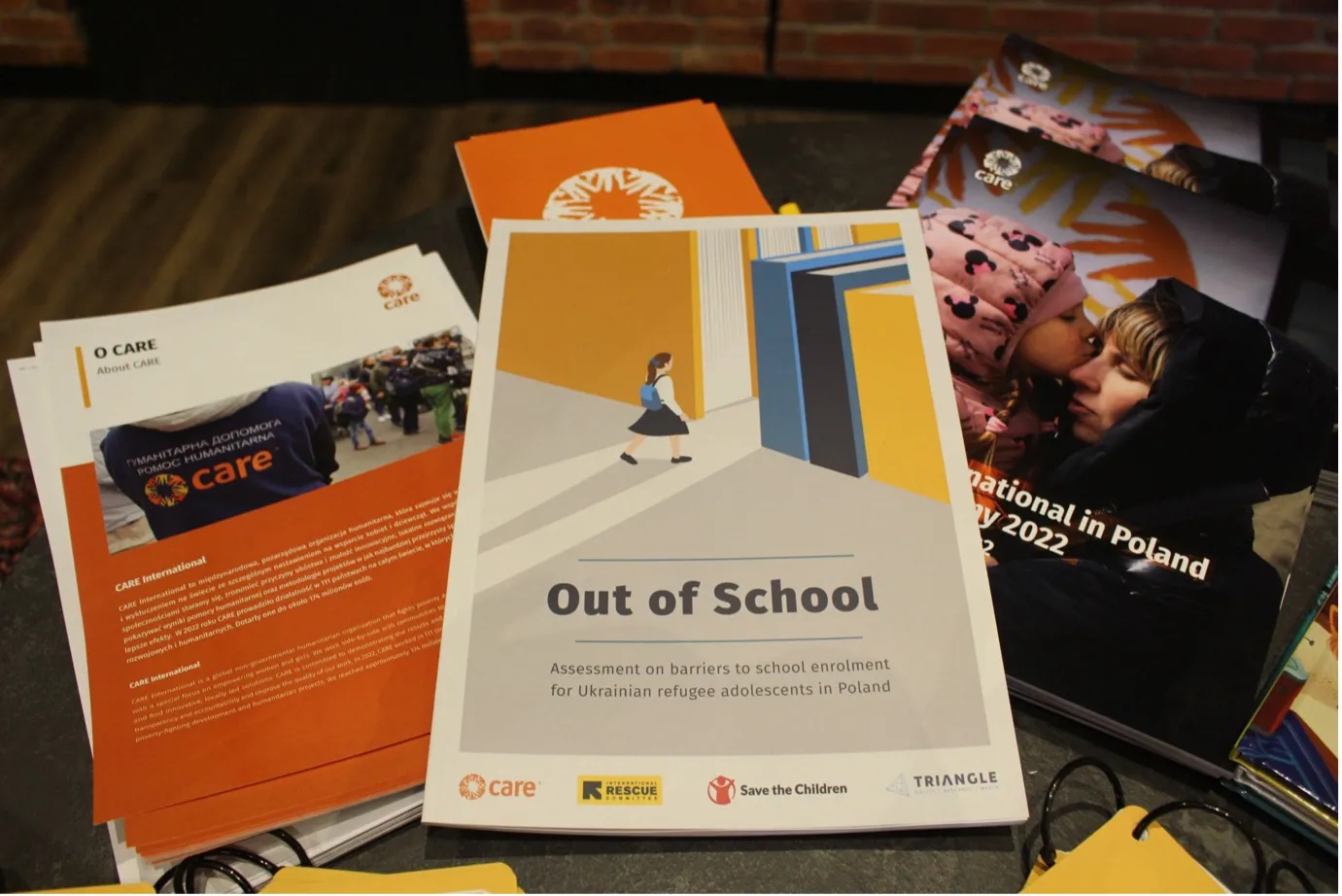

CARE Poland, led by Piotr Sasin, has been making an impact on the lives of Ukrainians since the conflict in Ukraine escalated on Feb. 22, 2022.

Now, more than two years later, the mission emphasizes integration for Ukrainian families – more than 1 million people, mostly women, children, and seniors – who have settled in Poland.

By now, over many days, months, and years, many families have been able to find stable housing and employment. But it is Ukrainian children and teens who are still finding this new life extremely challenging.