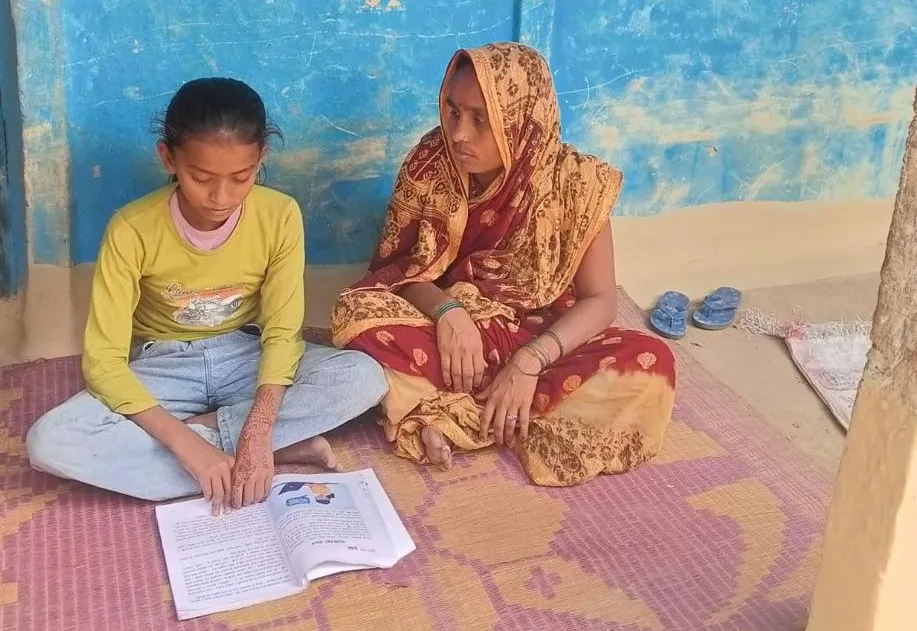

Twelve-year-old Radhika Yadav wasn’t talking about a distant possibility. The fear was immediate and real. She had reason to worry.

In Nepal, where 5 million girls are child brides, with 1.3 million married before age 15, education isn’t just about learning — it’s about survival.

For girls like Radhika — from underserved communities including the Musahar, Dalit, and religious minorities in Madhesh and Lumbini provinces — access to education is especially scarce. One program that offers a rare lifeline is UDAAN, a Nepalese word meaning “flight” or “flying high.”

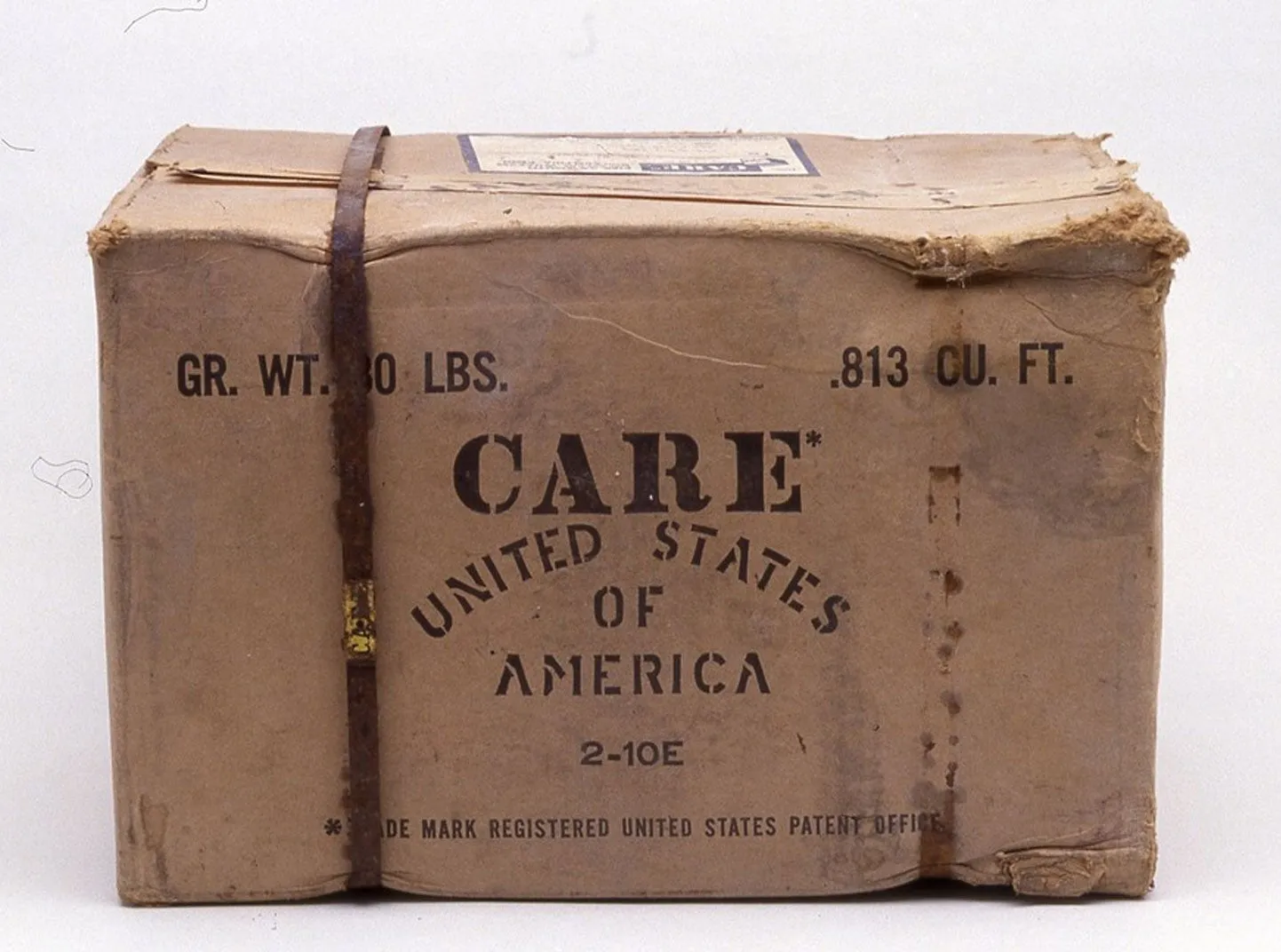

UDAAN, also known as SOAR in other countries, is CARE’s specially designed education program for girls ages 10 to 14 who have never attended school or who have dropped out early. Through an intensive 11-month curriculum, it gives them a second chance to transition into formal public schools. Operating across 13 learning centers, the program provides education, leadership and life skills, academic support, and practical services that keep girls enrolled. UDAAN also gives girls a chance to delay or avoid early marriage, because quality education enables girls to make informed decisions about their lives.

Radhika had finally found her place. After years out of the classroom, the UDAAN center provided the refuge she needed, a place where she built friendships, gained confidence in her abilities, and reignited her excitement for learning.