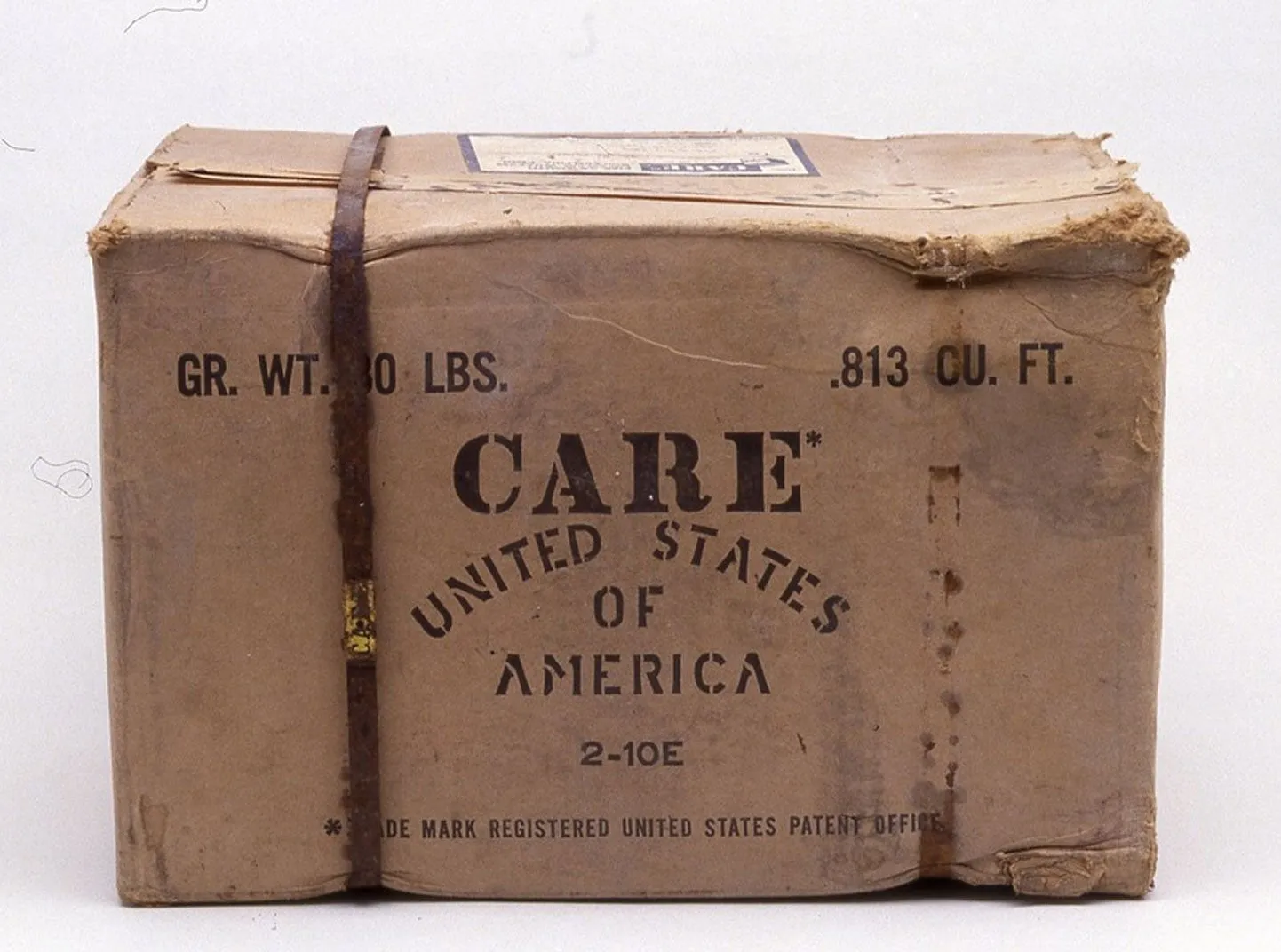

By the time Nany reached the Colombia–Ecuador border, the journey had grown even more precarious. Despite the efforts of the migrant movement and the NGOs that support them, such as CARE, last year, Ecuador introduced stricter entry requirements for Venezuelans. This has left many migrants in legal limbo and has made the already difficult journey even more dangerous.

The border guard looked at her expired Venezuelan ID and shook his head. Nany remembers his words so clearly. “He said ‘You can’t enter. You’ll have to go back.’”

She had no money to return. Shocked, unsure of what to do next, Nany handed her cousin her phone — the only thing of value she owned — so she wouldn’t be completely alone.

“I told her, ‘Take care of yourself. Do things right,’” Nany remembers. “I thought, ‘Maybe it’s not my time. I’ll go back to my daughter and we’ll try again.’”

Her cousin cried and begged her not to leave. Nany hugged her, told her to go on, and turned back toward the guard, preparing to retrace her steps to Venezuela, to Yancy, to everything she’d been trying to escape.

Then something unexpected happened.

“It was a miracle,” she says, light growing in her eyes as she remembers. “The guard stood up. He looked at us and told me to go ahead. ‘If anyone asks,’ he said, ‘you and I never saw each other.’ And that’s how I entered Ecuador.”

It was a moment of grace she still holds close.

“I arrived with a bag of saints,” she says — a small collection of devotional images and figurines for protection and comfort — “and three rags: one dress, one pair of shorts, and underwear. But I arrived with faith. I needed faith for my daughter. It wasn’t about education or work. It was about the chance for her to live.”

First day, first kindness

In central Quito, bright blue buses arrive daily, carrying people who have left everything behind in search of safety and stability. Nany arrived among them — afraid, alone, and uncertain of what came next.

“I was afraid to get on the bus,” she remembers. “Afraid to walk alone. Afraid to go out and sell things.” She pauses. “Xenophobia was my biggest fear.” She worried that Ecuadorians would see her as a burden, as someone who didn’t belong.

Yet her first day in Ecuador also marked the beginning of what Nany now calls “seven wonderful years,” even though her daughter was still far away.

That day, she met Alexandra Maldonado, founder of Las Reinas Pepiadas, a women-led organization supporting Venezuelan migrant women in Ecuador, and a local parter of CARE.

“Alexandra was like an angel,” Nany tells us. “She hugged me and said, ‘Welcome to your new home. Are you here to work?’”

In a moment when Nany expected rejection, she found acceptance and opportunity from an Ecuadorian women. She told Alexandra she could make arepas, the cornmeal staple of Venezuelan cuisine, rich with memory and meaning. The very next day, Alexandra helped her secure her first catering job.

Arepas are more than food. They’re culture, memory, home. Reina epiada — a dish named after a Venezuelan beauty queen that inspired the organization’s name — is an arepa filled with chicken, avocado, and mayonnaise. For Nany, making arepas in Ecuador wasn’t just a way to earn money. It was a way to say, “This is where I come from. This is who I am.”

“Sharing my culture through food helped ease my fear,” she says. “People didn’t point fingers at me. They said, ‘This is delicious. Thank you.’ And I thought, I’m in the right place.”

“For me, Reinas is family,” she adds. “It’s the safe space that welcomed me when I arrived in Ecuador. It’s the place that gave me the opportunity to grow, to feel secure, and to create a safe home for my daughter.”

Even with that solidarity and support, Nany’s first months were difficult. She struggled with depression and loneliness, longing for the day Yancy would join her.

Their reunion came sooner than expected. With support from Las Reinas, Nany was able to bring Yancy to Ecuador just six months after arriving. Her daughter was hospitalized for her heart condition almost immediately. The procedures she needed, the ones they couldn’t access in Venezuela, were all successful.

The power of adaptation