Either Fatima and her daughter needed to make the journey on unpaved roads, dodging armed conflict, looters, robbery, and worse, or the medicine needed to come to her.

“My 19-month-old daughter was so small, suffering from repeated bouts of diarrhea and skin diseases,” said Fatima. “I was aware that the health clinic in my area had run out of medical supplies for weeks due to the continued conflict.”

“I was afraid that I might lose my extremely sick daughter, like other children who died because of merely preventable diseases.”

In the Marrah Mountains of Central and South Darfur, people have suffered through decades of conflict, limiting access to basic social services. Because of the formidable security and logistical challenges, only a few humanitarian agencies are operating. For CARE Sudan, getting staff and medical supplies to the Marrah Mountain area remains a major challenge.

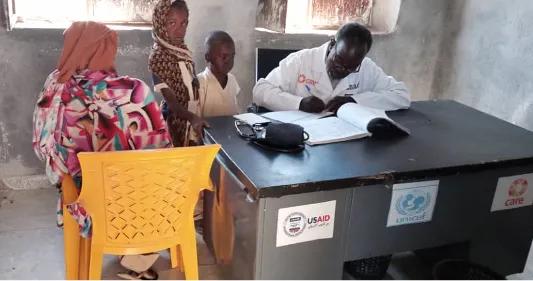

“I was so worried as I received reports that pregnant women were bleeding to death during delivery and children were dying due to lack of medical supplies,” said Sakina Ahmedi, a physician with CARE Sudan.