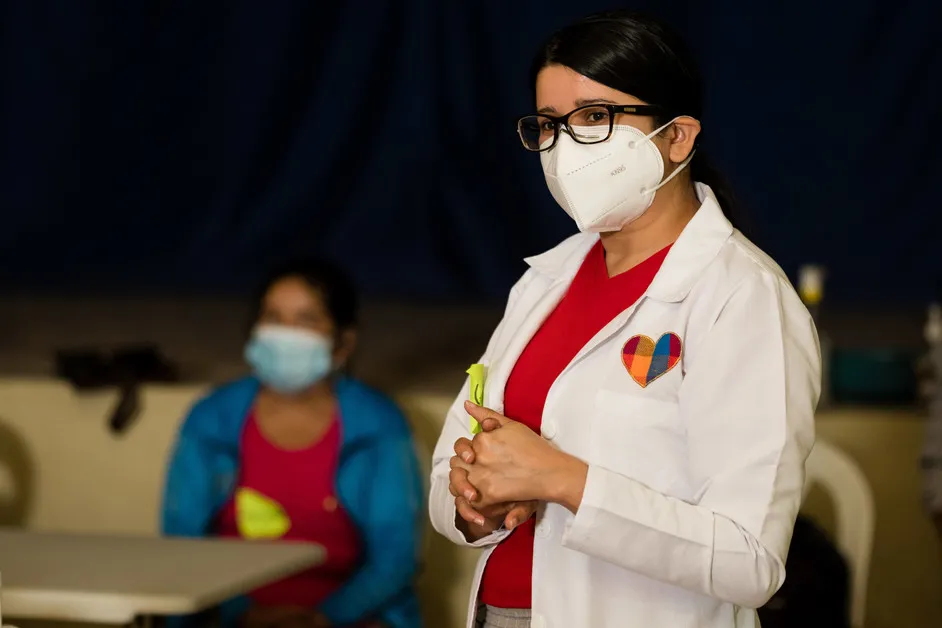

We know that women and girls are particularly impacted whenever crises hit, and COVID-19 is no exception.

CARE has worked for over 75 years at the nexus of development and humanitarian issues. Our presence in over 100 countries — with COVID response work in 69 of them — has shown us the critical need to put gender at the heart of all we do, and the enormous return on investments when we follow this principle.

Now three years after the COVID-19 virus was first detected, the pandemic’s devestating impacts continue, and women are bearing the brunt of the burdens. Even so, the United States’ updated COVID-19 Global Response and Recovery Framework fails to consider these gendered realities.

The only way to equitably respond and recover from COVID-19 today and to prevent and prepare for health challenges in the future is to put gender at the center.

CARE’s She Told Us So (Again) report, released in March 2022, makes clear that the impacts of COVID-19 globally are worse than they were in September 2020.

CARE spoke with over 22,000 people (including 17,363 women) in over 23 countries and found that, for the women and girls CARE works with, the confluence of lingering COVID impacts and disruptions, lack of tailored response, and other crises including climate-related emergencies and the global food crisis, have made their situation worse.