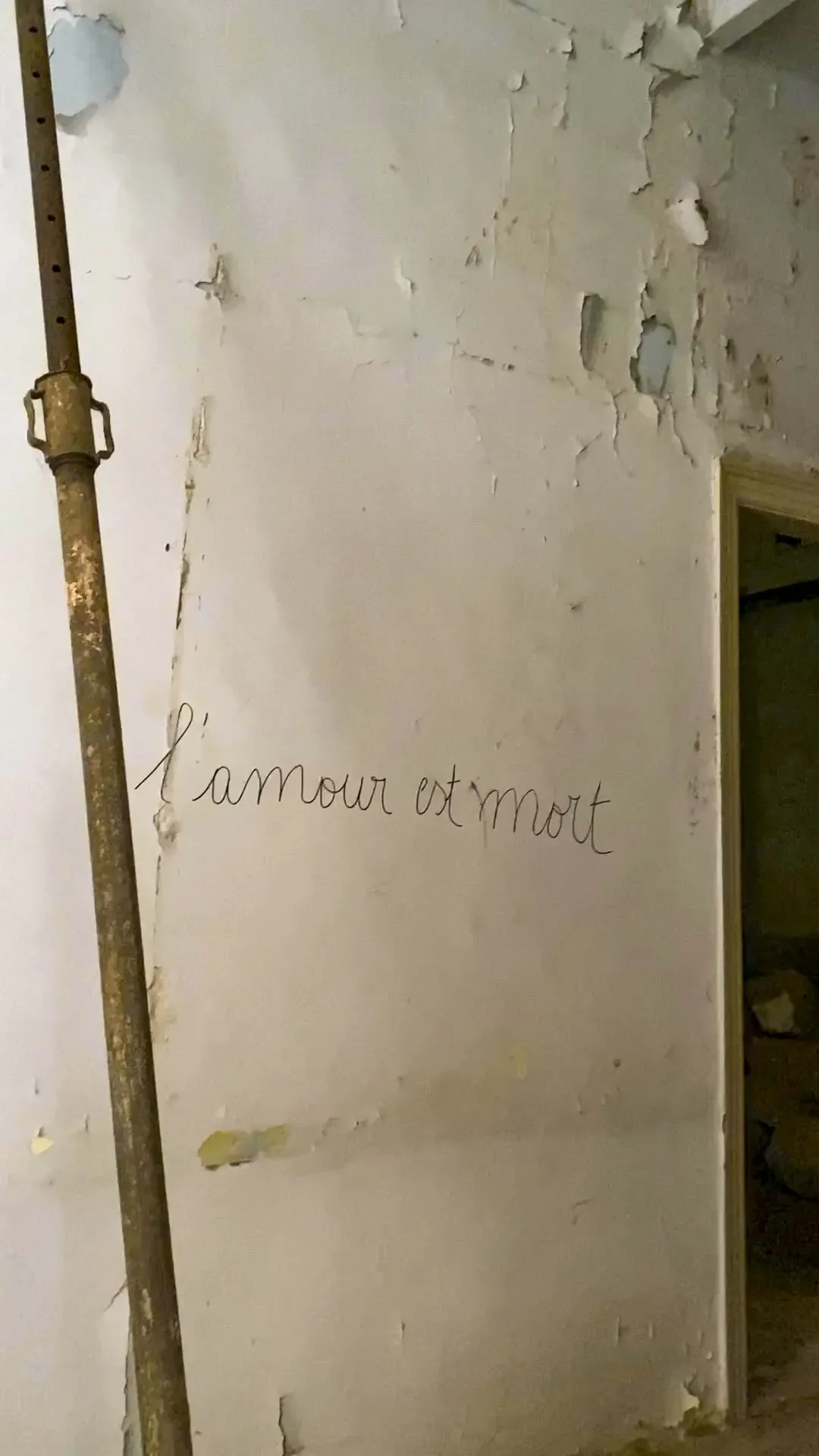

Hundreds of buildings remain as broken ghosts of their former lives, their owners lacking the funds to repair them. All of the rubble, stacked just off the streets, was moved by residents and the droves of people who came from around the country to help their neighbors, rather than government agencies.

The blast was the third disaster to rock the population of Lebanon in less than a year.

The first was in the fall of 2019 with the devaluation of the Lebanese pound (LBP), the result of high levels of debt, a large fiscal deficit, a stagnant economy, and a deteriorating balance of payments. At the same time, Lebanon faced a period of political instability and social unrest. The government’s inability to implement necessary reforms and address the underlying issues further eroded confidence in the country’s financial stability.

Before the devaluation one U.S. dollar bought 1,500 Lebanese pounds; today, the practical street exchange rate is one-to-100,000 and the inflation rate is running at 264 percent. The majority of the population are unable to make ends meet.

The second is familiar: the global spread of COVID-19 which resulted in 1.2 million cases and 11,000 deaths in Lebanon.

While those numbers may pale in comparison to other places, if you consider that Lebanon’s population is 5.6 million people, the number of cases represents roughly one-fifth of the population. Using that equation, it would mean 20.7 million Americans infected.