Where the crisis hits hardest

As the multi-layered humanitarian crisis deepens, women like Nurta bear the brunt. As more water sources dry up, women and girls are forced to walk long distances and to wait long hours to get to what remains.

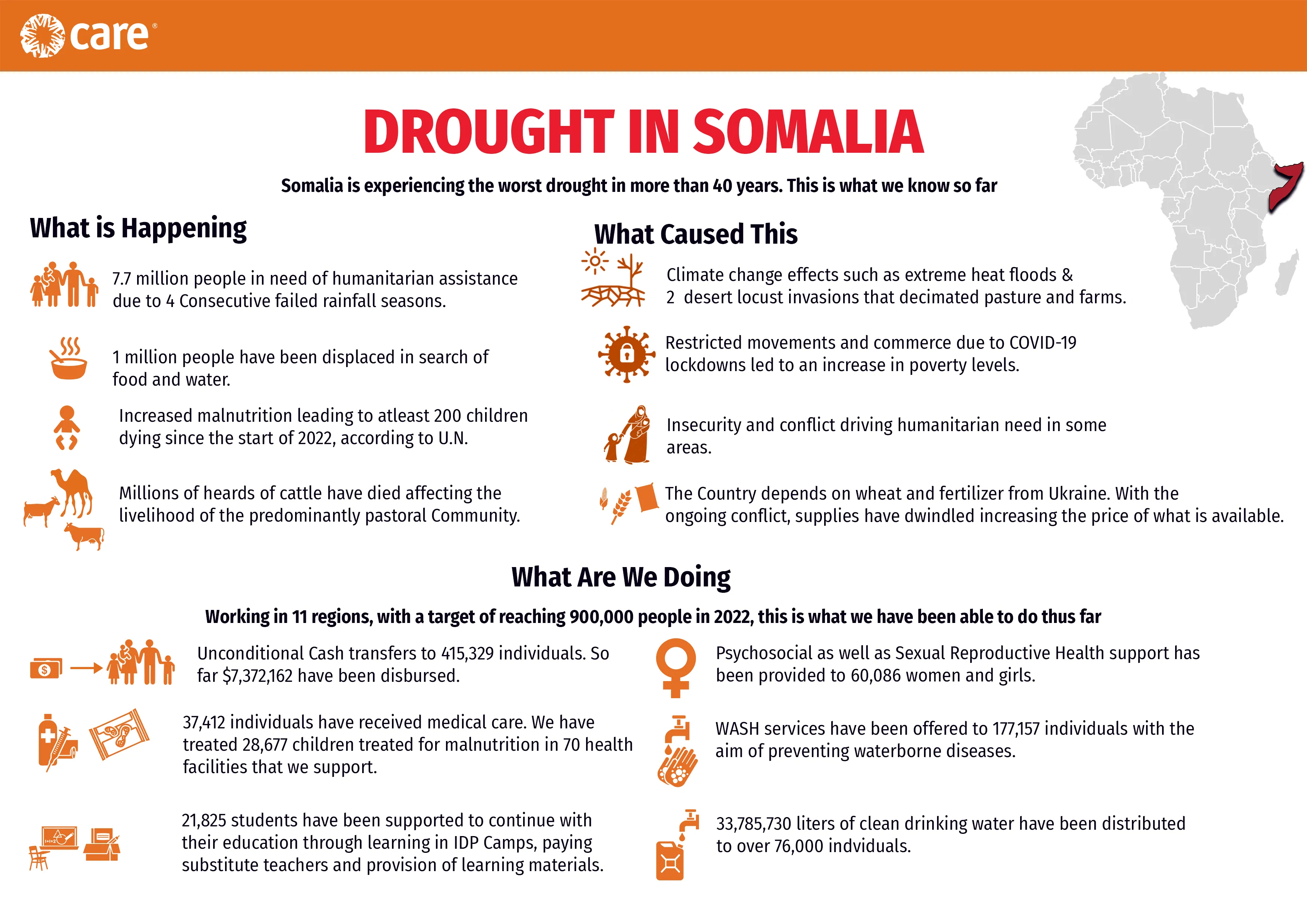

In addition, the costs of water have increased along with fuel prices, which further limits access for many vulnerable households. Livestock rearing, which forms the backbone of families like Nurta’s incomes, has been particularly hard hit. Families have lost hundreds of thousands of animals due to lack of water and pasture.

“For communities in Somalia, another famine is unthinkable,” says CARE Somalia/Somaliland Country Director Iman Abdullahi.

“For families who endured the last famine, this is a nightmare repeating itself.”

CARE is scaling up its response to the crisis through health and nutrition programs like the one in Dhobley, as well as assistance with water, sanitation, and hygiene around the country. CARE is also providing food and livelihood support in the form of cash and vouchers, so people can choose how best to prioritize their household finances.

“The humanitarian community put out various warnings and raised alarms over the past two years, yet we failed to avert a catastrophe,” Deepmala Mahla, CARE USA vice president for humanitarian affairs, says. “But it is never too late to respond and save lives.”

CARE hopes Nurta’s success story becomes one of many in Somalia, but the need for help continues to grow.

“The nurse still calls me to follow up, and she gives medication and health advice,” Nurta says. “Now I can care for my children, and I’m able to walk and do the daily work my family needs.”

To learn more about CARE’s work in Somalia, please visit CARE’s disaster response page.